We get mixed reactions when we describe our one-to-one learning model that pairs one teacher and one student, working together. Some people see it as the absolute in a range. If study after study have shown that smaller class sizes lead to better educational outcomes, then a class size of one is the best possible approach. Others are more skeptical. What about collaboration and group work? they ask. Won’t my child field lonely and miss something critical by being all by herself? Do these negatives outweigh the positives?

With a couple hundred classes under our belt at this point, we’ve done some reflecting on these ideas. Here’s why we’re so bullish on one-to-one learning.

Enhanced Focus

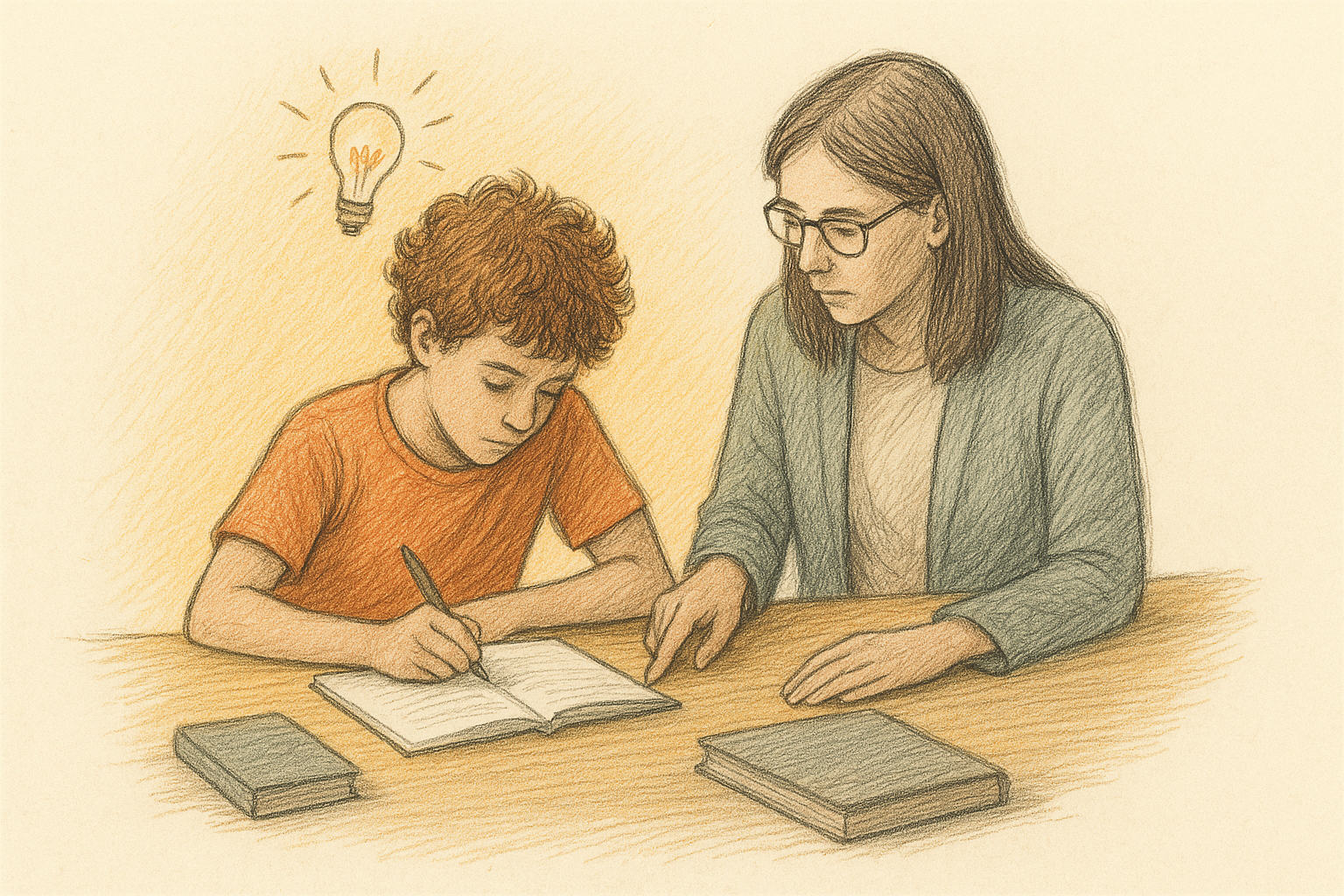

One of the first things that happens in a one-to-one learning environment is that students and teachers become focused on the work at hand. Gone are the distractions and disruptions that are euphemistically called “classroom management” in a traditional classroom and which studies show can absorb up to 50% of class time. The one-to-one learning model claws back this time, and allows the educator to focus on the student, and vice versa

“One-to-one is incredible,” shares Lance Billingsley, a math and science educator who taught for many years at the Green School in Bali and is now a teacher with Cicero. “I’ve never been able to connect with students so deeply and to build a plan for them so quickly.”

Personalization

A key piece of one-to-one learning is that it frees up the teacher to completely personalize the course to the student, to meet her where she’s at, and to build lesson plans tailored to her. In a classroom a teacher has to gear learning to the mean. But, most students don’t conform to a mean. They occupy ends of a U curve on either side of that mean—some charging ahead, some needing more support. But, in a group setting the educator is limited in how much she can serve those students.

One-to-one completely changes this. If the student is flying, the teacher gives him wings. If the student is drowning, the teacher has a life-ring and scaffolding for her. This is truly student-centered learning.

Most students don’t conform to a mean. They occupy ends of a U curve on either side of that mean—some charging ahead, some needing more support

Lance shares a story about his work with a ten-year-old math student. At the start of the course he designed the plan to cover certain concepts and follow a textbook. But, the student had a hard time connecting with the material. It felt “too much like school,” he related. Hearing this, Lance pivoted—on the spot. Out went the textbook and an admittedly more traditional approach, and in came math games and brain teasers to get the student excited about problem solving and figuring things out. Lance’s strategy became emergent rather than prescriptive, iterated weekly. Suddenly the student was on fire, telling his mom that his time with Lance was his favorite part of his day.

Afterwards Lance reflected that the one-to-one learning model “gets closer to what educators want, which is to narrow the gap with students and keep the focus on them.”

Student-Teacher Bond

One of the defining characteristics of teenagers is the gap that widens between them and adults. A lot of this is good and natural. Teenagers need space to define themselves. But, at the same time, an adult—in particular, a third party adult that isn’t a parent—can provide valuable mentorship, modeling, and friendship. Sometimes this gap narrows for kids and they get close with a teacher. They build a bond of trust, which can unlock a huge amount of learning. Some of us may have experienced this ourselves: Building a bond with a teacher during our teenage years. Finally, someone got us, we felt; and through this bond we got turned on to school. It was rare. But, when it happened it was pivotal to our lives as learners.

This is an everyday thing with one-to-one learning. In the absence of distractions, where “there’s no place to hide,” a teacher-student bond forms quickly, and becomes a defining feature of the Cicero model. Although on the face of it 120 minutes of live interaction each week (most of our courses meet twice weekly for one hour) doesn’t seem like a lot of face-to-face time; but it is intense time. It’s one-on-one, incredibly focused, private conversation, away from the public stage, where a teen can open up, and where a talented teacher can find areas of common ground upon which to build a strong relationship.

“There’s a lot to love about the one-on-one model,” shared a parent recently. “But, maybe the biggest piece is the bond that formed between [my son] and [his teacher]. We’ve never seen him so alive, so engaged. He can’t stop talking about school.”

Co-Learning Dialectic

We believe that learning is a lifelong journey. In primary, middle, and high school we are at the beginning of that journey, and what we learn is as much about how to undertake that journey—how to learn, how to remain curious—as it is about the actual stops—content, pieces of knowledge—acquired along the way.

The fundamental monad of one-to-one learning is the dialectic: A conversational exploration between student and teacher that seeks to uncover the truth of a subject. In modern pedagogical parlance, this is often called “co-learning” in which the teacher is a guide or mentor for the student, modeling how to learn.

In a group setting it can be challenging to build a co-learning culture because teachers feel more pressure to lecture at students rather than engage them in conversation. (At a certain group size, conversation is impossible.) But, in one-to-one this dynamic is flipped. Lecturing feels weird in this context; co-learning more natural.

The Importance of Solitary Work

So far we’ve been talking mostly about learning in an environment where there are two people, teacher and student, engaged in deep discussion, dialogue, maybe even a dialectic. But, at Cicero, where classes are typically designed with one or two live sessions each week and a little bit of back and forth by email or WhatsApp, this constitutes about 2 hours of a total of 4-6 hours of work each week. The student executes the remainder of the work on her own; and since so many Cicero students are homeschoolers or worldschoolers, a lot of this solo work is done in a solitary setting.

The image of our kids working alone like this freaks us out. We worry that they’ll become shut-ins, unable to function socially. But, what we forget is how critical solitary work and quiet reflection is to an intellectual pursuit. Zena Hitz, a tutor at St. John’s College (the “great books” school) and author of Lost in Thought: The Hidden Pleasures of an Intellectual Life says that at its heart learning is a personal thing. In a recent interview with David Perell Hitz articulates the unique value of quiet, solitary work, and how as a society we’ve come to devalue this. Learning in a social setting is important; but when we’re with others we show our social selves. We’re aware of how we come across, what we’re saying, and what people think about what we’re saying. It’s important—critical, actually—to pull away from the social fabric for a time (you can never fully escape your social self) and come to a place “where you’re connecting with yourself as having a value that’s independent of how people are judging you.”

“Learning starts with me, my desire to learn,” says Hitz. “We need to connect with ourselves as people with our own sets of questions, our own trajectories, our own sources of meaning.” And the best way to do this is by curling up with a book on your own, in a quiet place, and really diving in.

Hitz also points out that even in this situation where you’re learning alone, you’re never actually alone. “There’s something communal in reading a book,” she explains. “You’re in corner, reading a book, and there’s someone with you. It’s the author. And the author is introducing you to other people, people the author knows, people they’ve read. And you’re entering into this social world. People may be dead. But there are other minds that you’re interacting with.”

Hybrid Pods

That said, we’re beginning to roll out hybrid pods (look for them in the 2023-4 school year), in which students continue their work one-to-one with their teacher, but also pod-up with other students for group work and collaboration. Our view is that group work like this is important, but not primary. One-to-one will still be primary to our model.

Solving 2 Sigma

In the 1980s the University of Chicago educational researcher Benjamin Bloom conducted a study of learning in which he compared a group of students learning in a typical group setting (15-25 student in a classroom) with students who were taught one-to-one; and then tested both groups. The results were staggering. Students who were taught one-to-one had learning outcomes that were two standard deviations higher than those in a group setting. Bloom called this the 2 Sigma Problem because while it was clear that one-to-one learning could deliver life- and society-changing results, in the 1980s, before internet and the work-from-anywhere revolution, no one could fathom how you could deliver one-to-one learning at scale.

This, of course, is exactly what Cicero does. We like to think of our model as a 2 Sigma Solution, in which students get twice as much learning and growth accomplished in half the time.

It’s early days yet and we don’t have a large data set; but, we believe that we can already see this in action. After a 18 months of one-to-one learning, most of Cicero students are far ahead of their peers in group settings.

Downsides

All this makes one-to-one learning sound like a panacea. While we believe that it is one of the most powerful options for families and learners today—especially those who need personalization—there are some challenges inherent in the model.

One key challenge is that the student has to onboard some healthy executive function skills. They have to be able to manage their calendar, manage their tech, show up on time, and work independently between live sessions. There’s no bell ringing to move them to the next class. They are their own bell. This can be difficult for new students, and so we provide some support in the form of a Unit Zero series of videos and pamphlets to help skill-up in these areas; and Cicero teachers weave it in to their courses.

We also provide a stand-alone course in executive function. This is one of our most popular courses.

Conclusion

We live in a time of unparalleled educational opportunity. The options that have bloomed for families in just the last two years are incredible. And, it’s no wonder that students are leaving traditional school in the highest numbers ever. For some of these one-to-one learning can be a key part of the mix, helping them reignite their love of learning, build powerful relationships with master teachers, and propel themselves academically towards a healthy future.